In 2006 Frontex deployed Hera, its first joint operation outside Europe, in an attempt to intercept migrants travelling by boat from Senegal to the Spanish Canary Islands. This made an already dangerous journey even more difficult and included the involvement in illegal pushbacks. Since then, the EU has intensified its efforts of turning African countries into EU border outposts and stopping migrants on the way to Europe before they even have a chance to claim asylum. In advance of the Abolish Frontex International Action Day on 18 December, this article provides an overview of Frontex’s activities on the African continent that are public knowledge.

What is the legal framework governing Frontex’s activities in Africa?

Operation Hera was the significant first step of Frontex’s expansion to the African continent and included maritime and aerial patrols in the territorial waters of Senegal, Mauritania, Cape Verde and Morocco. However, the operation’s scope was limited in that the agency was at that time not allowed to operate on land in the country itself or disembark the migrants it intercepted on its shores. But the tides have turned and new regulations that came in force in 2016 and 2019 now make this possible. For operations outside the EU (which can involve uniformed and armed Frontex personnel), Frontex can now conclude a so-called status agreement with the country concerned. These are formal international agreements concluded by the Council of the EU in cooperation with the European Commission and with the consent of the European Parliament, and after consulting the EU Fundamental Rights Agency and the European Data Protection Supervisor. Frontex already has such agreements with many countries in the Western Balkans, where it also started operations, and is currently negotiating agreements with two African countries, namely Senegal and Mauritania. However, the new Frontex executive director Hans Leijtens said in September that he is reluctant to launch such operations in Africa.

But even without status agreements Frontex is already undertaking various activities on the continent, including stationing liaison officers and launching networks aimed at collecting as much data as possible concerning potential migrants. The agency has also concluded various working arrangements with countries and EU missions, which are less formal than status agreements since they only require the EU commission’s approval. These working arrangements include information exchange, strengthening of the border security and control capacities of the third country, and return agreements, making deportations from the EU possible.

Where in Africa is Frontex active and what is it doing there?

Liaison Officers

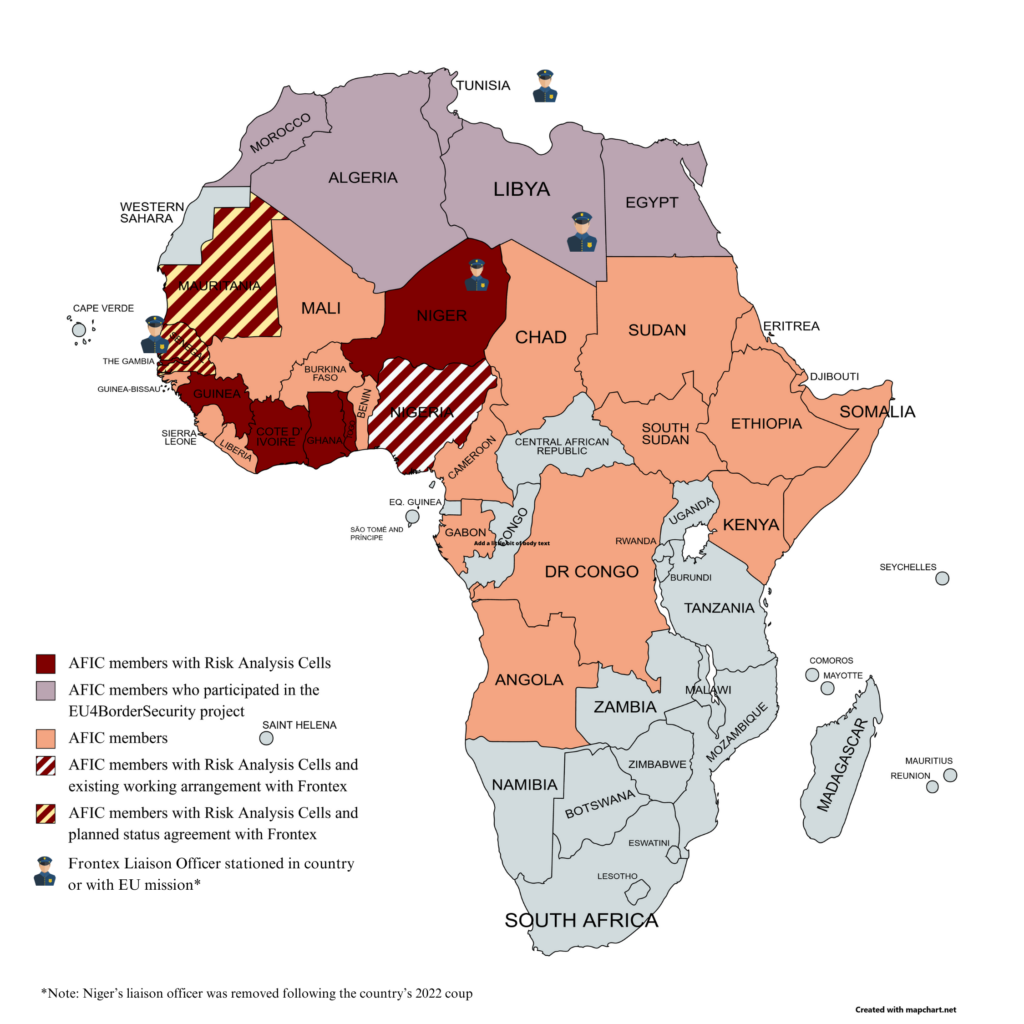

Frontex currently has liaison officers stationed in Senegal (since 2019), with the EU Border Assistance Mission in Libya (EUBAM, since 2018), and with the EU naval military mission NAVFOR Med Sophia that patrols the Mediterranean sea off the coast of Libya. Liaison officers communicate with responsible national authorities, exchange data and intelligence, and, in the case of Senegal, coordinate deportations. As part of its working arrangement with EUBAM, Frontex has also trained the so-called Libyan Coastguard, a militia responsible for abducting people at sea and forcing them into inhuman detention centres.

Frontex also had a liaison officer stationed in Niger since 2017 that was however removed following the coup in July 2022. Similarly, a 2022 working arrangement with the EU Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) mission EUCAP Sahel Niger with the aim of preventing migration through the West African country is currently being reconsidered.

The AFIC and risk analysis cells

The Africa-Frontex Intelligence Community (AFIC) is an informal network open to all countries in Africa that was set up in 2010. A project to strengthen this network received €4 million EU taxpayer money between 2017-2023. Most recently it counted 30 member states that participated in workshops, trainings and conferences with the aim of increasing their cooperation and information sharing on border monitoring and control.

Eight countries in the AFIC have established so-called risk analysis cells. While the cells are run by the African states’ border management authorities, Frontex provides the participants with equipment and training and sets up integrated border management systems, which aim to make their national databases interoperable with EU databases. The idea is to give Frontex access to information about who is crossing a border and when, thus surveilling migrants long before they even get close to EU borders. As Verfassungsblog writes, this information makes it easier for Frontex to exert pre-emptive border control and to facilitate deportations. For example, a person pushed back to Libya who does not have identification papers might have had their fingerprints recorded by one of Frontex’s risk analysis cells before their departure, and could thus be deported from Libya to their country of origin. In 2022, Frontex announced the end of the project and the handover of equipment to border police analysts working for the risk analysis cells of the eight AFIC countries.

Other activities and future plans

Negotiations are currently ongoing for status agreements with Senegal and Mauritania, which would enable armed Frontex officers to perform executive tasks such as conducting border checks, preventing people from entering the countries if they do not have the right papers, and conducting deportations. Reportedly, the planned status agreement with Senegal is supposed to include legal immunity for Frontex officers from persecution for crimes they commit during their work. This is already a common feature of the status agreements with Balkan countries.

Apart from that, according to Verfassungsblog, ‘Frontex is furthermore planning working (not status) arrangements with other governments in North and East Africa. Libya is of particular interest; after such a contract, Frontex could also complete Libya’s long-planned connection to the surveillance network EUROSUR. With a working agreement, the border agency would be able to regularly pass on information from its aerial reconnaissance in the Mediterranean to the Libyan coast guard, even outside of measures to counter distress situations at sea.’ Frontex already has a working arrangement with Nigeria.

In recent years Frontex has also intensified its relations with Morocco, working for example on cooperation with its coast guard. Via the EU4BorderSecurity project, which ran from 2019 to 2021 with €4 million funding from the European Neighbourhood Instrument, Frontex worked on strengthening border security capacities in all countries in North Africa.

What are the consequences of Frontex’s activities in Africa and the externalisation of EU borders?

Frontex is already implicated in pushbacks and human rights abuses in the central Mediterranean Sea as well as the Aegean, with barely any hopes for victims of these violations to ever hold the agency accountable. Operations so far from the EU will make this problem even worse. The externalisation of EU borders to African countries has already led to preventable deaths and immense suffering. In Libya, Frontex has passed on information and geolocations of migrants to militias that force them into detention centres notorious for severe human rights violations including slavery and sexual abuse. In Northern Niger, the EU helped draft a law that illegalised migration in a region where people have always (legally) migrated for work, leading to the deaths of thousands of people in the desert and destroying the traditional transport economy. In Tunisia, the EU wants to pay a racist autocrat to crack down on migration, which means deporting people to the desert where they die from heat and thirst. While Israel is bombing Gaza, the EU’s biggest worry is not how to protect Palestinians from genocide and war crimes, but how to keep them away from EU borders in the unlikely case they manage to escape their open-air prison. For that purpose, the EU now seeks to replicate its Tunisia deal with Egypt.

While migration is a solution, not a problem, Frontex portrays people on the move as a security threat, for example by conflating migration with human trafficking and crime. The cooperation with EU Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions, both military and civilian, further blurs this line and contributes to the securitisation and militarisation of what should primarily be a humanitarian policy field. By operating in countries that are not even bordering the EU, it also conflates internal and external security. Frontex also uses this securitisation narrative as a reason for not providing information to the public, which leads to a lack of transparency about its activities in Africa and a lack of opportunity for affected people to protest against them. Frontex blocks access to documents for people without EU citizenship, which are the very people most affected by Frontex’s expansionist activities.

Andrei Popoviciu raises another issue: ‘[…] now the EU hopes to extend Frontex’s reach far beyond its territory, into sovereign African nations Europe once colonized, with no oversight mechanisms to safeguard against abuse.’ Indeed, by using development money as a reward for border fortification, the EU is applying a carrot-and-stick approach that reeks of neocolonialism. Its focus on hard borders has already disrupted mobility in regions were free movement used to be legal and necessary for regular economic activity, such as the ECOWAS region that allows people to move from one West African country to another without needing to obtaining visas. To understand how outrageous this approach is, imagine West African leaders pushing for Germany and France to reintroduce border controls between the two countries and sending money, equipment and liaison officers to supervise this process.

Finally the EU’s obsession with stopping migration far from its borders does not address the root causes of why people have to leave their homes in the first place. Instead, under EU pressure, and with money and equipment donated by the EU and its member states, African countries reinforce and militarise borders that were once drawn by colonial powers eager to extract the continent’s riches. The ruthless exploitation of natural resources and human labour continues to today and is one of the actual causes that forces people to flee their homes in the first place. Others are the Western support of authoritarian regimes, arms exports, unfair trade agreements and debt burdens, and the consequences of climate change: Man-made crises that could be tackled if only the political will existed.

How to take action?

On 18 December 2023, Abolish Frontex will hold its next International Action Day with a focus on Frontex in Africa. Find out how to participate here.

Resources

- Webinar: Externalizing the EU Borders: Frontex and Other Security Actors in West Africa, Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dCjEHGUSwEY

- How Europe Outsourced Border Enforcement to Africa, In These Times, https://inthesetimes.com/article/europe-militarize-africa-senegal-borders-anti-migration-surveillance

- The Territorial Expansion of Frontex Operations to Third Countries, Verfassungsblog, https://verfassungsblog.de/the-territorial-expansion-of-frontex-operations-to-third-countries-on-the-recently-concluded-status-agreements-in-the-western-balkans-and-beyond/

- Status agreement with Senegal: Frontex might operate in Africa for the first time, Matthias Monroy, https://digit.site36.net/2022/02/11/status-agreement-with-senegal-frontex-wants-to-operate-in-africa-for-the-first-time/

- Migration from West Africa should not be a crime, D+C, https://www.dandc.eu/en/article/detriment-senegals-people-their-government-supporting-migration-policies-eu

- Africa-Frontex Intelligence Community: participating agencies named, Statewatch, https://www.statewatch.org/news/2022/september/africa-frontex-intelligence-community-participating-agencies-named/